BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front)

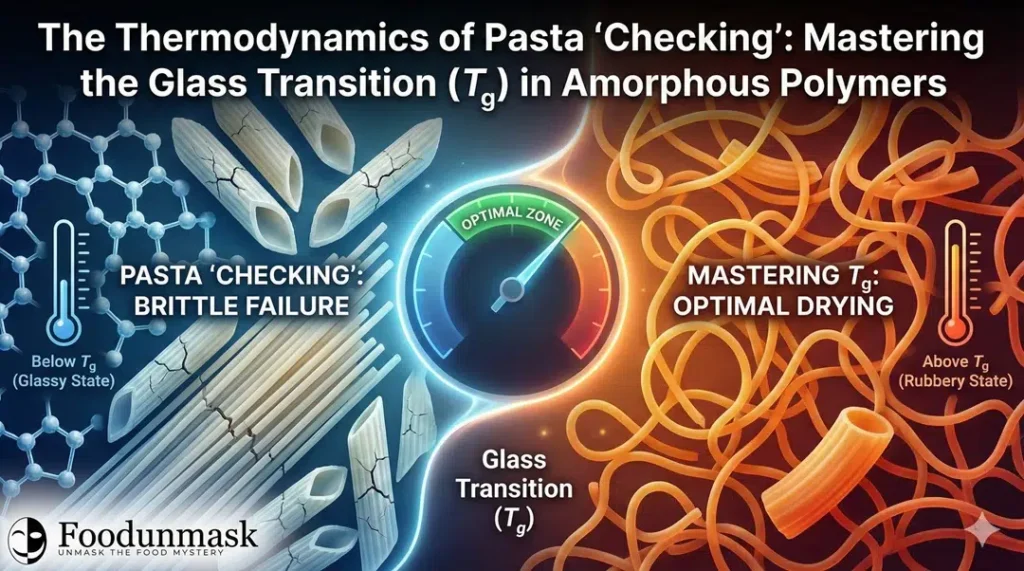

“Checking” (micro-cracking) is a catastrophic structural failure in dried pasta caused by differential internal stresses. It occurs when the product’s surface transitions from a flexible, “rubbery” state to a brittle, “glassy” state, while the core remains mobile. Preventing this requires treating pasta as an amorphous polymer and engineering a drying curve that maintains the product temperature above its moisture-dependent Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) until internal moisture equilibrates, ensuring a uniform transition to the stable glassy state.

Key Takeaways

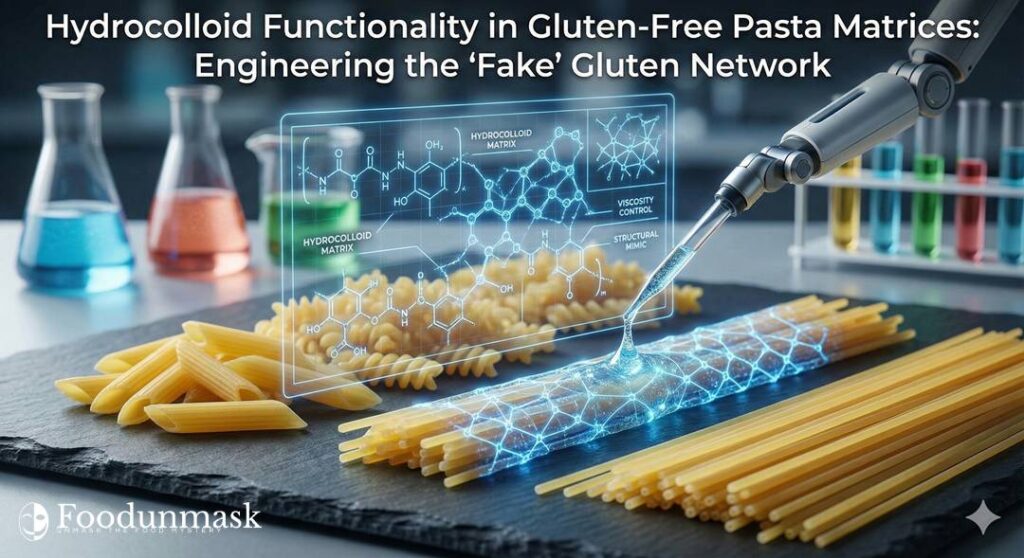

- Material Definition: Pasta is not a crystalline solid; it is a semi-crystalline, amorphous biopolymer system consisting of a protein network and embedded starch granules.

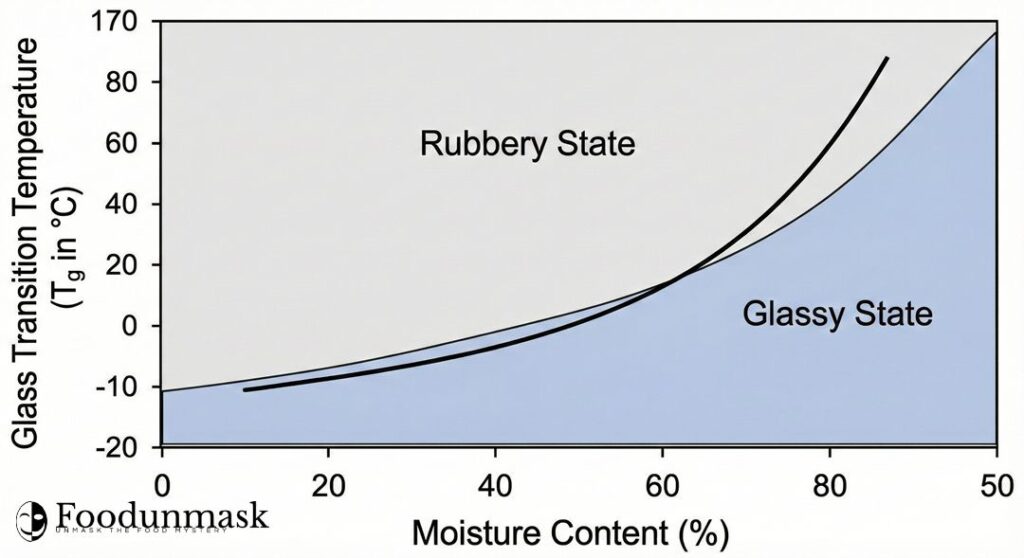

- The (Tg) Factor: The Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) is the critical boundary where the polymer chains lose mobility. Tg is inversely related to moisture content; higher moisture content corresponds to a lower Tg.

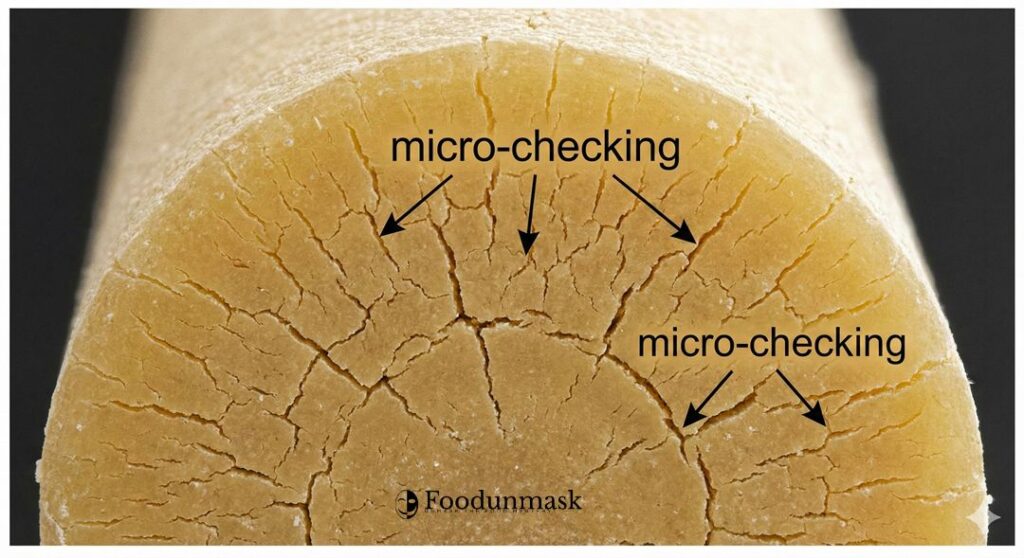

- The Failure Mode: Checking occurs when the drying rate exceeds the moisture diffusion rate. The surface dries, its (Tg) rises, and it becomes a rigid glass, while the wet core shrinks, pulling against the brittle surface until fracture occurs.

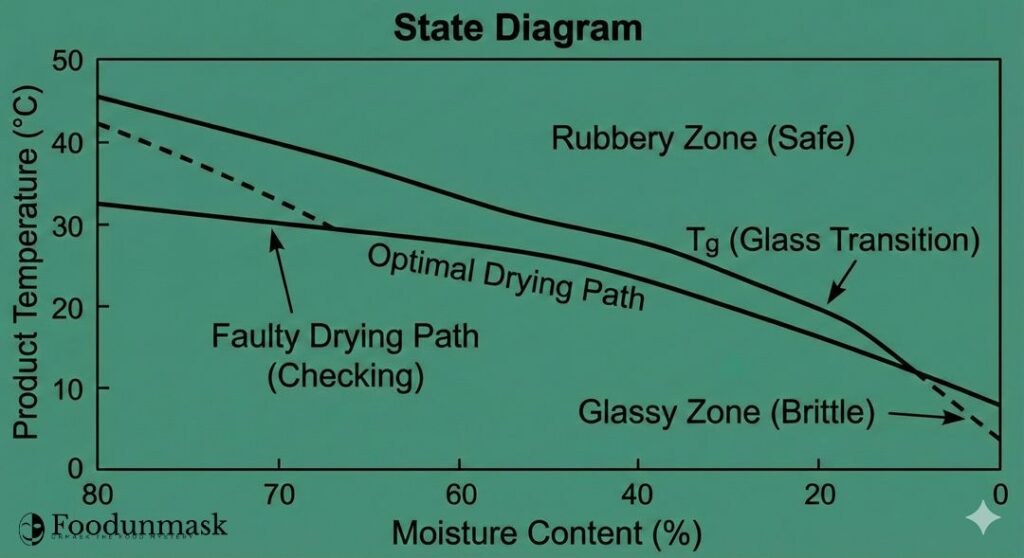

- The Solution: The drying process must be governed by a “State Diagram,” mapping temperature against moisture content to keep the product in the safe “rubbery” zone until the final drying phase.

The Physics of Failure: Why Pasta Cracks

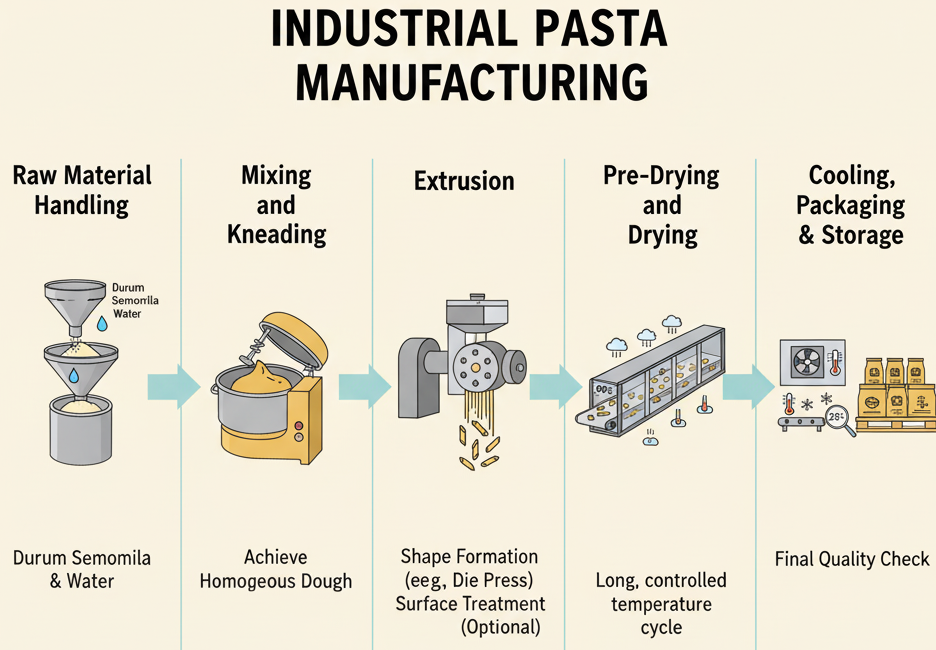

In polymer physics, pasta dough is defined as a viscoelastic system. During drying, it transforms from a malleable dough (high moisture, >30%) to a rigid solid (low moisture, <12.5%).

Checking is not a chemical defect; it is a thermomechanical failure. It arises from the competition between heat transfer (supplying energy for evaporation) and mass transfer (water migrating from core to surface).

When water evaporates from the surface faster than it can diffuse from the core, a moisture gradient forms. Because pasta shrinks as it dries, this gradient leads to differential shrinkage. The surface tries to shrink more than the core. If the surface material is rigid (glassy) while the core is still contracting, tensile stress builds up at the interface. When this stress exceeds the tensile strength of the pasta matrix, energy is released as fractures.

2. The Mechanism: The Glass Transition (Tg) Explained

To prevent checking, we must control the phase state of the pasta. Amorphous polymers exist in one of two states, defined by their temperature relative to their Glass Transition Temperature (Tg):

- Rubbery State (Temp > Tg): The polymer chains (gluten and gelatinized starch) are mobile. They can slide past one another. In this state, the material is flexible and can absorb stress without fracturing.

- Glassy State (Temp < Tg): The polymer chains are virtually immobile (“frozen”). The material is rigid, hard, and brittle.

The Water (Tg) Relationship

Crucially, water acts as a plasticizer. It inserts itself between polymer chains, increasing free volume and mobility. Therefore, as the moisture content decreases, the Tg of the pasta increases.

- Wet Pasta (30% moisture): Tg is below room temperature (e.g., 0°C). It is rubbery and flexible at ambient conditions.

- Dry Pasta (12% moisture): Tg is high (e.g., 60°C). At room temperature (25°C), it is a rigid glass.

The danger lies in the transition period where the surface is dry (high Tg), and the core is wet (low $T_g$).

The Engineer’s Tool: The State Diagram (Rubber vs. Glass)

The “State Diagram” is the process engineer’s roadmap for defect-free drying. It maps the (Tg) curve against the actual product temperature during the drying cycle.

The goal is to keep the entire pasta cross-section (surface and core) in the Rubbery State for the majority of the drying process. In this state, the polymer network is mobile enough to relax stresses caused by shrinkage.

If the surface temperature drops below the (Tg) line while the core is still wet, the surface becomes glassy. It loses the ability to relieve stress. As the core continues to dry and shrink, it pulls against this rigid surface shell until it cracks.

The optimal drying curve maintains a product temperature Tp such that Tp > Tg until the moisture gradient is minimized. Only then should the product be cooled to ambient temperature, allowing the entire noodle to transition into the glassy state simultaneously.

You can see the further state diagram here.

Operational Strategy: Navigating the Drying Curve

Modern pasta drying utilizes high-temperature (HT) or ultra-high-temperature (UHT) drying cycles (>70°C) specifically to manage the glass transition. By keeping the drying temperature high, the pasta remains far above its $T_g$ during the critical phase of rapid moisture loss.

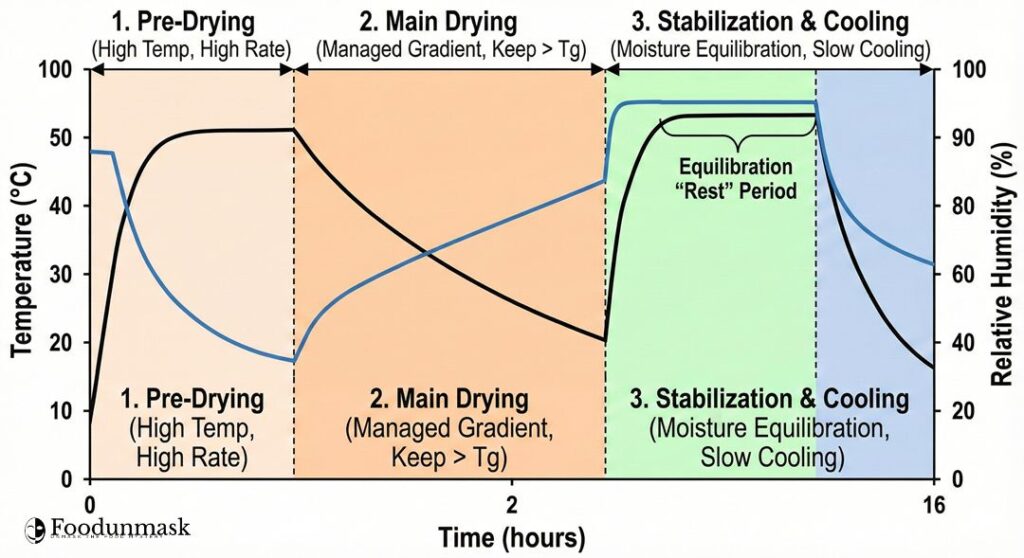

The strategy involves three key phases to navigate the state diagram:

- Pre-Drying (Surface Setting): High heat and airflow rapidly reduce surface moisture, creating a thin, permeable skin. The product is wet and hot (Rubbery).

- Main Drying (Moisture Diffusion): The core of the process. Temperature and humidity are balanced to maintain the moisture gradient essential for drying without letting the surface cool below its rising (Tg). The product is kept rubbery to allow for shrinkage stress relaxation.

- Final Drying & Stabilization (Equilibration): This is the most critical phase for preventing checking. The drying rate is drastically reduced. The goal is to allow the core moisture to diffuse to the surface, equilibrating the moisture profile throughout the strand. Once equilibrated, the pasta is slowly cooled, allowing the entire cross-section to simultaneously cross the (Tg) threshold into the glassy state.

[Practitioner’s Corner]: The Stabilization “Rest” Period

“The most common cause of checking in industrial settings is rushing the final stabilization phase. Operators often see the target average moisture (e.g., 12%) and immediately move to cooling.

Do not terminate based on average moisture alone. You must program a ‘rest’ or ‘sweating’ period at the end of the curve, characterized by high humidity (75-85% RH) and moderate temperature (50-60°C), for 1-2 hours. This stops surface evaporation and forces internal moisture equilibration. Only after this rest period should the active cooling phase begin.”

[Regulatory Alert]: Moisture Content Limits

While thermodynamics dictates the process, regulations dictate the endpoint.

- USA (FDA): 21 CFR 139.110 states macaroni products must have a moisture content ranging from 11% to 12.5%.

- Global Standards (Codex Alimentarius): Generally specify a maximum moisture content of 12.5% for dried pasta intended for long-term storage to prevent microbial growth (mold).

- Disclaimer: All drying processes must be validated to ensure the final product meets both quality (no checking) and safety (low water activity) standards.

Yes. In fact, the Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) is a property distinct to amorphous polymers (or the amorphous regions within semi-crystalline polymers). It is the specific temperature range where the disordered polymer chains gain enough thermal energy to slide past one another. Crystalline regions do not exhibit a (Tg), they only melt (Tm).

The (Tg) of amorphous Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) typically falls between 67°C and 81°C (approx. 153°F – 178°F). The exact value depends on the degree of crystallinity, moisture content, and the method of measurement (e.g., DSC vs. DMA).

It is the critical thermal threshold where a polymer transitions from a hard, brittle, “glassy” state to a soft, pliable, “rubbery” state. Below (Tg), the polymer chains are “frozen” in place; above (Tg), they possess the mobility to rotate and stretch.

No, not in the strict thermodynamic sense. Unlike melting (a first-order phase transition), (Tg) is a kinetic transition. It does not involve a release of latent heat (enthalpy). Instead, it represents a change in heat capacity (Cp) and free volume over a temperature range, which is why the measured value can shift depending on how fast you heat or cool the material.